Heightened competition and unpredictable results in this year’s college admissions cycle

The class of 2021 faced an unprecedented year of college admissions as a result of the coronavirus pandemic.

With newly implemented test-optional policies and an unprecedented surge in the number of applicants, college admissions for the class of 2021 made history for its heightened level of competition and seemingly unpredictable results. Mr. Jeff Selingo, author of New York Times best-seller book Who Gets In and Why: A Year Inside College Admissions (2020), spoke to the Sacred Heart Greenwich community via Zoom April 13 to share his insight about the changes in this year’s college admissions process, and to provide his expert opinion about the causes of these differences.

One of the biggest changes in this year’s college admissions process was the inability of applicants to take standardized tests from March 2020 due to the start of the coronavirus pandemic. In past years, the majority of colleges have required students to submit these scores or the admissions officers would not consider their application. However, due to COVID-19 and the transition to distance learning across the country, thousands of students were unable to take these tests. This led to more than 1,600 four-year colleges choosing to waive the requirement for students to submit SAT or ACT scores when applying to their college, according to The Wall Street Journal.

As a result, there was a substantial decrease in the number of applicants who sent their standardized test scores to colleges. Last year, 77 percent of students who used the Common Application to apply to colleges submitted standardized test scores with their application, however, only 46 percent of students chose to do so this year, according to The Wall Street Journal.

Although test-optional colleges maintained that they considered all applicants equally regardless of whether the student submitted test scores or not, early acceptance data at some schools suggests that admissions officers viewed students who did submit test scores as more competitive in the applicant pool. For example, the University of Pennsylvania admitted 15 percent of those who applied in its binding early decision round, and 75 percent of these students did include test scores with their application, according to The Wall Street Journal. In the applicant pool as a whole, only two-thirds of the students submitted their test scores to the University, indicating that those who did submit scores likely had an advantage and were more competitive in consideration.

Mr. Selingo commented on the nature of test-optional admissions and how a lack of a test score might have been a disadvantage for some students in this year’s admissions cycle.

“At highly selective schools particularly, think about your application as a case to be made,” Mr. Selingo said. “You’re making a case in front of a judge, and you want as much evidence as possible. That means, for many students, you need as many of these strong signals of your potential as possible, and for many, that could mean a test score. If you come from a really good high school and a higher income background, the expectation is that you are going to have a test score because their assumption is you don’t have a test score because you didn’t score well. This doesn’t mean that you won’t get in, but you’re going to have a higher bar to get over at some of these schools that are test optional. Particularly these schools that just went test optional for the pandemic are looking a bit more skeptically at students who come from these rockstar high schools who don’t have test scores.”

In talking to admissions officers, Mr. Selingo was able to gain insight on the data behind test-optional admissions and what it meant for applicants this year.

“Generally, here is what I’m finding in schools new to the test optional movement this year,” Mr. Selingo said. “Probably about half of their applicants applied test optional. In almost all of these cases that I’m seeing, the admit rate with test scores was higher than the admit rate without test scores. In some cases, it was quite different. Colgate University, for example, admitted twice as many students with test scores than without.”

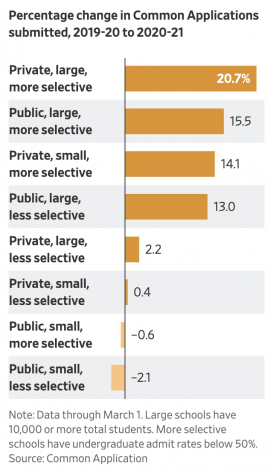

Overall, the country’s most selective four-year colleges and universities, including private and public schools, saw a 17 percent increase in applications this year, according to The Wall Street Journal. Specifically, more selective private universities received 20.7 percent more applicants, while less selective public universities of the same size received only 13 percent more applicants. For example, Harvard University received 42 percent more applicants compared to the class of 2024. In a year with much uncertainty and no guarantees, students who likely never would have applied to universities like Harvard due to their standardized test scores now thought “why not?” and submitted their applications. This thought process can account for much of Harvard’s 17,000-applicant increase for the class of 2025 and highlights the cascading effects of pandemic-induced uncertainty.

Despite individual schools seeing exponential increases, the number of overall applicants applying to college only rose 2 percent. Essentially, there was not necessarily a larger applicant pool, but that students were applying to more schools than in previous years, according to The Wall Street Journal. This phenomena is likely due to the fact that students were unable to visit many schools throughout their junior year and beginning of their senior year due to travel restrictions. Without usual campus visits and all around uncertainty, students found it difficult to decide which schools they wanted to apply to, causing them to apply to more schools overall.

Colleges ranked outside of the top 50, private and public alike, are not seeing the same increases in their applicant numbers. By contrast, many of these schools struggled to get enough applicants. The State University of New York system saw a 20-percent decline in their number of applicants, the largest annual decrease in the system’s 73-year history, according to insidehighered.com. Loyola University Maryland was down 18 percent in non-binding early action applications, forcing them to extend the application deadline, waive their application fee in certain cases, and provide a faster decision notification timeline. Ultimately, these colleges had to strike a balance between maintaining the same level of competition as in past years while also admitting more students in order to retain the size of their incoming class.

As the coronavirus pandemic had fueled a surge in applications, specifically at the most selective institutions, the acceptance rates of Ivy League universities became even smaller than in previous year’s. In the regular decision round, Columbia University accepted 3.7 percent of applicants as opposed to 6.1 percent last year, while Harvard only accepted 3.4 percent, a 1.5-percent decrease from last year’s admit rate, according to The Washington Post. Test-optional policies and the resulting higher number of applicants likely contributed to these microscopic acceptance rates, emphasizing the heightened level of competition in this year’s applicant pool.

In addition to the change in standardized test policies, complicated grade-point averages (GPAs) also impacted the ability of college admissions teams to make a confident decision about a student. Many high schools offered pass-fail options in the spring of 2020 as the coronavirus pandemic and the switch to distance learning changed their learning environment. With no test scores to submit and GPAs that are incomparable to past years, college admissions offices lacked key data points in their consideration of students, according to The Wall Street Journal. Last spring, students also faced the cancellations of their sports seasons and extracurricular activities, leaving a gap of leadership positions and community involvement in their applications.

In light of a hectic year of college admissions, Mr. Selingo shared words of advice for the class of 2022 and how the students can alleviate some of the stress and anxiety that comes with the college admissions process.

“What’s important is to have a balanced list,” Mr. Selingo said. “There are more than 20 schools out there. To me, lower the anxiety level starts much earlier in the process. It is important that you know you have a good group of schools that are a good fit socially and financially and that you can imagine yourself at many of them. If you start the process there and timebox it a little bit in how much you talk about it and how much you are invested in it, I think there is less anxiety throughout the process.”

Featured Image by Natalie Dosmond ’21

Natalie is thrilled to be the Editor-in-Chief for the King Street Chronicle this year. She is looking forward to engaging with the staff writers and pioneering...