From October 25, 2016 to January 29, 2017, the second floor of the Bauhaus-esque building of the Met Breuer chronicled the narrative of African American culture in an exhibition titled “Mastry.” The artist Mr. Kerry James Marshall was born in 1955 and lived his early years in Birmingham, Alabama at the cusp of the civil rights movement, which had a profound influence on his painting subjects.

“Part of the history of black people in the western hemisphere, in some ways, has been fleeing from this notion that they were black. So I can represent an ideal, and with that you can demonstrate that there is nothing to be afraid of, nothing to run from, and that, in fact, a good deal of beauty resides there,” Marshall said, according to interviewmagazine.com.

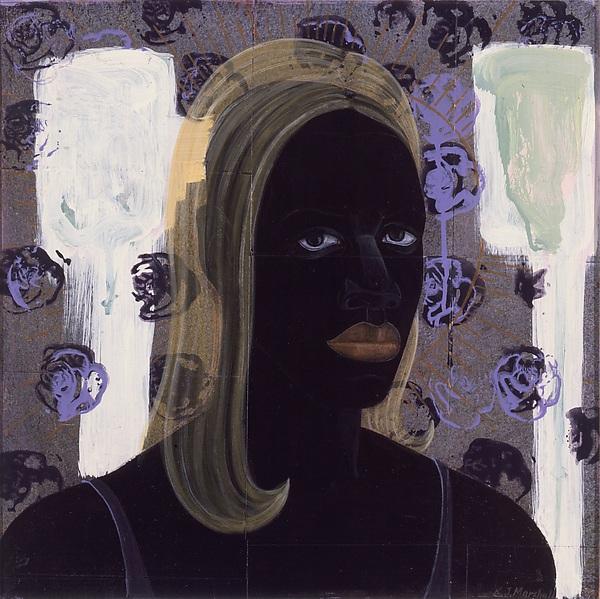

His large scale paintings boldly demand attention. The most striking feature of his art is the deep ebony skin tone he selects for his subjects. To Marshall, the dark skin represents the oppressive shroud that makes his culture invisible and indistinguishable to the white man’s gaze. Marshall’s deliberate choice of skin color is a defiant yet celebratory homage to what it means to be black in America. This motif is a nod to Ralph Ellison’s novel Invisible Man (1952), wherein the dark-skinned protagonist recognizes that his color makes him invisible to his surroundings, according to The New York Times.

Yet, the arresting open eyes of each subject address the viewer directly to offer a glance into the soul, preserving the subject’s humanity. It seems as if the flash of a camera shutter has paused each scene, jousting its subjects from their routine.

In an interview with the Met Museum, the artist himself notes the lack of African American subjects in the Metropolitan. Recognizing this, he challenges himself to assimilate his often forgotten and glazed over origin into the westernized canon.metmuseum.org.

“I don’t expect those people to have made pictures about me because I wasn’t a part of that culture and I wasn’t a part of that history,” Marshall said, according to

Consequently, he paints scenes of his cultural experience to fill in the missing pieces.

He masterfully meshes traditional composition and contemporary style to create dynamic narrative scenes. This is apparent in his piece titled Studio, 2014, in which he examines his role and position as an artist.Taking the imposed vision of the artist in his working space, as in The Painter’s studio by Gustave Corbet, Marshall flips implied perception on its head and replaces the central figure — the artist in control — with a woman, using a vivacious red frame to draw the viewers’ eyes in. A subtle nuance that I enjoyed is the striking texture of the paint that drips on the canvas, invading the viewers’ space. This technique compellingly reverses an artist’s approach to create an illusion of depth.

Many Mansions,

The exhibit also featured works from his series “Garden Project,” such as

(1994.)“We think of projects as places of despair. All we hear of is the incredible poverty, abuse, violence, and misery that exists there, but there is also a great deal of hopefulness, joy, pleasure, and fun,” Marshall said, according to artic.edu.

In the background, shadowed structures mirror the Chicago’s Stateway Gardens, or “IL2-22” in red paint. The entry sign to the commons is covered in a shroud of flowers growing up from land the subjects tend, perhaps representing the actions that they take to fight the connotation that surrounds them. In the painting, the words “bless our happy home” embellish a ribbon which two bluebirds carry, reaffirming the sense of communal, peaceful living amongst the subjects.

A stark contrast to examining project housing, Marshall again suggests a flip of the assumed societal structure in Past times, (1997). The banner, a celebrated motif throughout his work, I believe suggests the strenuous hard work that merited the leisure activities the characters enjoy, predominantly seen by the

artist as white leisure activities. Thus, Marshall challenges a racially charged social hierarchy.

Coming from a Catholic upbringing and having an appreciation for art curation, I immediately noticed a very interesting detail in De style (1993). The central figure assumes the classic pose of the Sacred Heart of Jesus — one hand is relaxed in the air in a blessing motion, and the other rests gently over the heart. Although, in his hand, he holds a clipper tool and stands behind a man in a chair, situated in a colorful patchwork of a barber shop. This painting handles not only the aspect of African American hair as a major centrality to cultural beauty, but also presents whimsical tones. On the far left of the scene, a woman sits next to a plant that reflects the exact shape of her hair.Purposefully situated next to De Style, Marshall’s painting Self-portrait of the Artist as a Supermodel (1994) juxtaposes the cultural aspect of styling African hair. The superficial ridiculousness of this painting amused me as I passed by, but after a closer examination, I realized the message was bitter. The translucent blonde, straight hair clearly represents the presumption of western beauty standards. Marshall criticizes what society views as beautiful and worthy of super-model status.

The New York Times.

I attended the exhibit in January, soon after the premier of the show. The exhibit was packed with art connoisseurs and appreciators alike, giving the exhibit rooms an energetic, eclectic atmosphere. Another aspect of the exhibit was selections of artwork the artist picked from the main Metropolitan Museum gallery such as works from the artists Ingres, Horace Pippin, Ad Reinhardt and Gerhard Richter, according to

These provided insight to the artist’s muse and inspiration, as the incorporation of classical artwork is evident in his work.

“Mastry” challenges conceptual ideals and celebrates African American culture to make the invisible visible and fill the missing images of the western canon.

– Nina Rosenblum, Staff Writer

Linda Vasu • Feb 27, 2017 at 4:05 pm

Thank you for this wonderfully scholarly piece about a very important artist, and I’m so happy you’ve included it in the KSC! It was an exhilarating exhibit, and I showed slides to the APEng/AdvStd Lit classes. Like writer Toni Morrison, Marshall aims to reclaim, include, and celebrate African-American experience as central to an understanding of what Morrison calls the American “Master Narrative.”

kev filmore • Feb 27, 2017 at 3:28 pm

Nina, I loved this exhibition and his incredible work! Thanks for writing about it. Ms. Filmore