COVID-19 has transformed the world into a classroom

Although most in-person classes are cancelled due to the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, students can still learn experientially, outside of the classroom.

This year, the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic has created a period of great uncertainty and enormous change. Although we have reshaped our definitions of work, shopping, and socialization, we, as a country and as a world, are struggling to redefine education. As politicians, principals, and parents fear that children will fall behind in their schooling and be unable to catch up, we must expand our perspective on and definition of education to better suit the present time.

Currently, 48 states in the United States of America either ordered or recommended that K-12 schools cancel in-person classes, according to edweek.org. As a consequence, school administrators, teachers, and students are transitioning to alternative educational models, many of which are based on websites, mobile applications, and video calls.

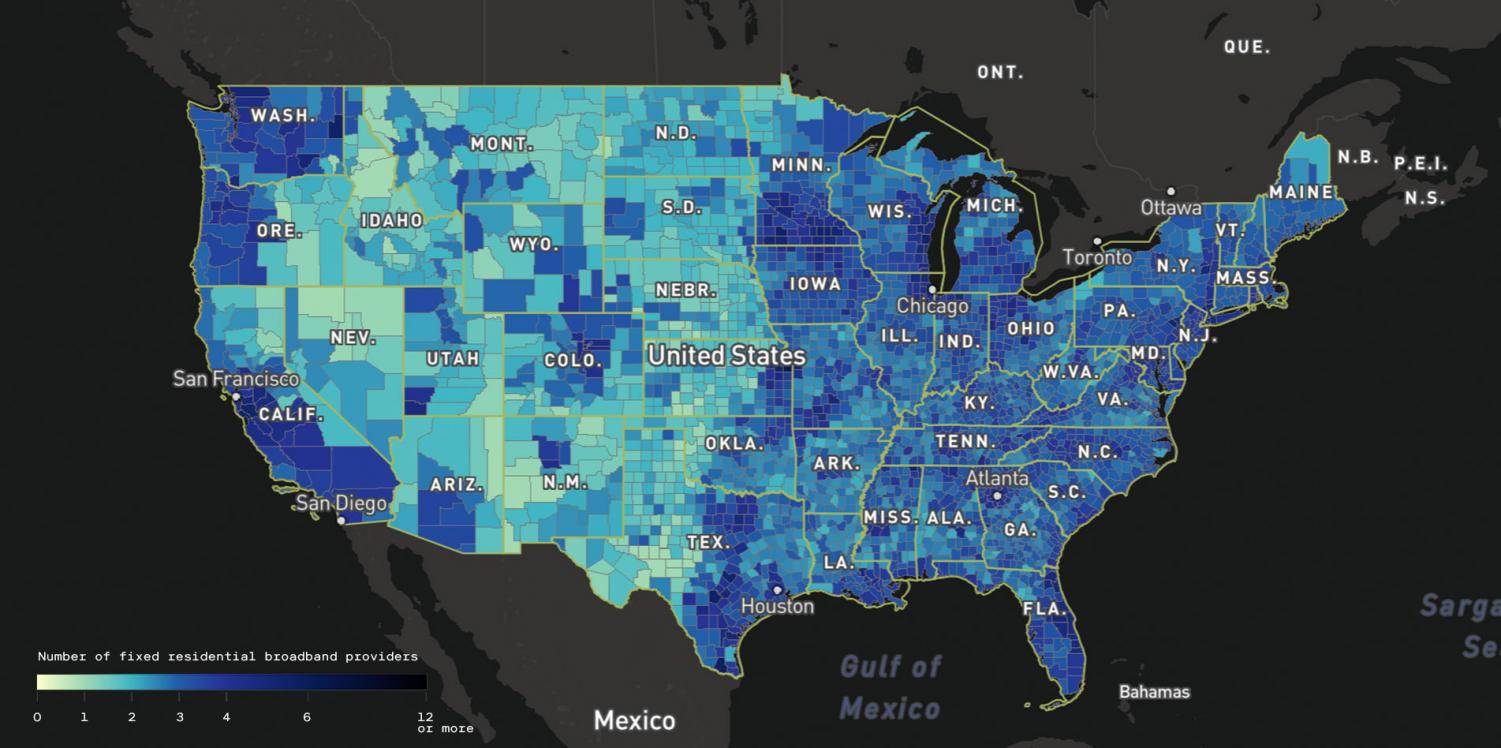

Though educators are working valiantly to create virtual assignments and lessons that keep students engaged and progressing, these are far from ideal. Students across the country, especially those living in rural areas, struggle with a lack of access to devices and the Internet. This prevents them from attending remote lessons and impedes their ability to complete assignments, according to usatoday.com. Moreover, a 2015 Stanford University study shows students enrolled in online schools learn and retain less information than their peers who attend traditional in-person schools, according to credo.stanford.edu.

These conditions have inaugurated a new term, “the COVID-19 slide,” a play on the concept of “the summer slide.” The latter refers to skills, specifically in reading and mathematics, that children do not retain during the summer months when they are not in school. Researchers with the Northwest Evaluation Association predict that the COVID-19 slide will have a greater negative impact on children than the summer slide, according to nwea.org.

Although I do not fall into the demographic most vulnerable to the COVID-19 slide, the coronavirus has still changed my educational experience. My courses have moved online, and I find it more challenging to learn new academic material through virtual classes.

During this time, though, I have learned more non-academic skills than I have in years. I learned to recognize bird species that I never knew existed. I can identify three new constellations without using a star chart. I now know how to sew face masks and fix my sewing machine when it breaks. I have tested new recipes and planted flowers in my backyard. More than ever, I have had to apply what I have learned at Sacred Heart about empathy, patience, self-reliance, and flexibility to my everyday life.

I cannot acquire such knowledge by reading a textbook. This is not fact-based learning, but knowledge I am gaining from life experience.

Over the past two months, I have heard multiple reporters and politicians on the television describe children as “behind” in their studies and education. Publications such as The Washington Post are going as far as to say that the COVID-19 slide will permanently set back an entire generation of students, according to The Washington Post.

Perhaps, though, the greatest risk is not that young students are academically behind, but rather that they internalize this label.

I find that people rise to expectations. If parents and professors expect young children to be behind, then they have nothing to which to rise. Yes, maybe they are behind, but that is only relative to the traditional educational system. Instead of labeling students as behind, we need to reshape our definition of education.

Rather than reading books about a fictional family, children are living those stories in their own households. They are practicing, not studying, kindness and compassion. They are asking questions, their curiosity still insatiable, about pathogens instead of polygons. After weeks of quarantine, perhaps they are beginning to look up from their computer screens to appreciate nature and interact with those around them. They are gaining invaluable knowledge from experience.

If we cannot expand our definition of education to call these children anything other than “behind,” then that is what we put them at risk of becoming. We need to realize that education is more than textbooks and classrooms. It is more than emailed assignments and video calls. If we reshape our mindsets and continue to encourage these children, then their education cannot and will not be stifled by a lack of Internet access, a highly-contagious virus, or months of quarantine.

Featured Image by Sydney Kim ’20

Sydney is honored to be a part of the King Street Chronicle leadership as the 2019-2020 Managing Editor, Opinions Editor, Podcast Editor, and one of the...

maria viale • May 23, 2020 at 9:42 pm

Excellent article Sydney!

I completely agree with you! Loved it!

gracias!

Sra Viale

Joyce Reed • May 23, 2020 at 1:24 pm

What a thoughtful and thought-provoking piece! I love that you are extending your learning into new areas and that the values you have learned at Sacred Heart supports you.